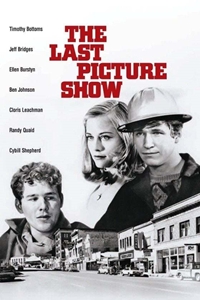

The Last Picture Show (R) ★★★½

The Last Picture Show is a character study in the truest sense of the term: a movie in which the narrative is just a mechanism by which we get to know the men and women inhabiting a small-town Texas community in the early 1950s. For director Peter Bogdanovich, this represented his third feature film (although one of the previous two was done under a pseudonym for Roger Corman) and showed him at the pinnacle of his creative powers. He would go on to make two more successful movies (What's Up Doc? and Paper Moon) before the roof caved in. The complete collapse of Bogdanovich's career may be unrivaled in Hollywood. Even Orson Welles didn't implode so quickly and utterly.

The Last Picture Show is a character study in the truest sense of the term: a movie in which the narrative is just a mechanism by which we get to know the men and women inhabiting a small-town Texas community in the early 1950s. For director Peter Bogdanovich, this represented his third feature film (although one of the previous two was done under a pseudonym for Roger Corman) and showed him at the pinnacle of his creative powers. He would go on to make two more successful movies (What's Up Doc? and Paper Moon) before the roof caved in. The complete collapse of Bogdanovich's career may be unrivaled in Hollywood. Even Orson Welles didn't implode so quickly and utterly.

The Last Picture Show is a rare movie that plays differently, but equally well, to members of separate generations. For those born in the mid-1940s and earlier, this is a nostalgia trip - a journey through memories unearthed in the nether spaces of the mind. For younger viewers - those who came into being after the second World War - The Last Picture Show is a time capsule to an era that, while not that long ago, is unlike anything that came after. 1951 Texas was a strange and contradictory place where a cultural war was being waged between the old and the new. Television was rising to challenge the preeminence of movie houses. The first shots of the Cold War had been fired and the United States was in Korea. Yet, in places like Anarene, vestiges of the Old West still existed, like the tumbleweeds occasionally seen blowing down the lonely streets.

In his 1971 review of The Last Picture Show, Roger Ebert wrote a personal essay steeped in nostalgia. The movie took him back to his teens (he was born in 1942), and stirred memories of what it was like growing up in Urbana, Illinois. For me, The Last Picture Show opens a window into a world that had all but vanished by the time I appeared on the scene in 1967. My earliest memories are from 1969 or 1970 - a time when the relative innocence of the 1950s had been overturned by the dual-pronged tumult of the sexual and civil rights revolutions. (This was also the time when Bogdanovich decided to look back and make this movie.)

The three principal characters in The Last Picture Show are graduating high school seniors preparing to make their way in the world. They are Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms), a naive boy who always seems to come out second man on the totem pole; Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges), a handsome but unfocused guy who has invested too much into a relationship with one girl; and Jacy Farrrow (Cybill Shepherd), a master manipulator whose wealth, good looks, and sexual curiosity allow her to acquire any boy she wants and discard him when she gets bored.

There are plenty of adults in Anarene, as well. The most prominent is Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson), who owns the pool hall, the diner, and the movie theater. Sam has a special bond with Sonny. In one of the film's most memorable films, the two go fishing in a pond where there are no fish (only turtles) and talk about life. Sonny is having affair with a lonely housewife, Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman), but she's more than 20 years his senior and is married to his high school coach. Lois Farrow (Ellen Burstyn) is an older, wiser version of her daughter, Jacy, and tries to offer some practical advice to her offspring - most of which is ignored. At 17, Jacy is rebelling, and her mother can only hope it doesn't end badly.

It's easy to forget that The Last Picture Show was filmed in 1971, not 1951. Set design and strong direction help the illusion, but no move on Bogdanovich's part was more critical than the decision to shoot the movie in black-and-white. That one simple stylistic decision transforms the film. With the exception of the nudity (which the Hays Code would have banned from a '50s production), it doesn't require much of stretch to believe that The Last Picture Show is a contemporary drama made in 1951 about characters living in a rural Texas town during that year. Viewers in 1971 were transported back two decades. Viewers in 2006 are taken back five and one-half decades. The year in which the movie is seen is irrelevant; once the film starts, the time is 1951.

The Last Picture Show explores the universality of aspects of the human condition, the most obvious of which is the need to connect. This is illustrated in the poignant, doomed affair between Sonny and Ruth, in the remembrances of Sam and Lois, and in the string of men who fall before Jacy. Everyone knows everyone else's business, but that's the nature of a small town. There are no secrets in Anarene, but that doesn't mean there's a lot of intimacy, either. Bogdanovich gets mileage out of this apparent contradiction. We suspect the community is too small to hold the likes of Jacy and Duane, but others, like Sonny, will live out their lives there.

With the exception of Ben Johnson, the veteran of numerous Westerns, the cast was comprised of fresh faces and character actors. Johnson rightfully won an Oscar for his work here. He is the glue that holds the film together. Sam may not be front-and-center for much of the running time, but he's as important a presence as any of the leads. The other Oscar winner is Cloris Leachman, whose lengthy resume prior to The Last Picture Show consisted mainly of television appearances. Her portrayal of Ruth is emotionally true, and more than a little heartbreaking. We can feel her loneliness, her hope, and her pain.

The film represented a break-out for Jeff Bridges, who was on the cusp of leaping to the A-list. For Cybill Shepherd, this was her big screen debut. She carries off the role of Jacy with the right mix of moxie and feigned invulnerability. The skinny dipping scene says all that needs to be said about her. Shepherd is good in this film, but her lack of range proved to be her undoing (and that of Bogdanovich, who was smitten with her and insisted on casting her inappropriately in a number of future productions) in subsequent features. She would eventually disappear in the late '70s only to re-surface opposite Bruce Willis in Moonlighting. A lack of star power and charisma prevented Timothy Bottoms from developing into more than a second-tier actor; his limitations are on display in The Last Picture Show. Despite being the central character, he is in many ways the film's least compelling individual, and his relationship with the mentally challenged Billy (played by Bottoms' brother, Sam) lacks emotional depth.

Bogdanovich adapted the screenplay from the novel by Lonesome Dove scribe Larry McMurtry. This should make it less surprising that there's the ghost of a Western hovering somewhere just beyond the edges of the screen. At times, The Last Picture Show looks like a Western. At other times, it feels like one. I'm sure the presence of Ben Johnson had as much to do with this as McMurtry's involvement, but the result is impossible to deny.

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M