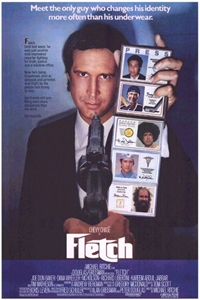

Fletch (PG) ★★

Fletch is an excellent case study about how something that may have worked in the 1980s no longer works today. Chevy Chase's slapstick antics, a screenplay tailored to his improv routine, and cheap production values make it hard to understand how this ever earned the label of a "cult classic." The film made a respectable $51M ($133M in today's currency) at the box office and about another 50% of that on home video, pushing it deeply enough into the black to warrant an unsuccessful sequel. Like many 1980s productions that developed a loyal following, the film's supporters present a passionate and compelling case for a movie that, taken on its merits, simply isn't very good.

Fletch is an excellent case study about how something that may have worked in the 1980s no longer works today. Chevy Chase's slapstick antics, a screenplay tailored to his improv routine, and cheap production values make it hard to understand how this ever earned the label of a "cult classic." The film made a respectable $51M ($133M in today's currency) at the box office and about another 50% of that on home video, pushing it deeply enough into the black to warrant an unsuccessful sequel. Like many 1980s productions that developed a loyal following, the film's supporters present a passionate and compelling case for a movie that, taken on its merits, simply isn't very good.

Fletch was, is, and always will be about Chase. The comedian essentially plays himself and has admitted to as much in interviews. He is allowed to improvise and anyone familiar with his stand-up routines will recognize how deeply the actor's comedic stylings inform this performance. In 1985, the inaugural Saturday Night Live cast member was at the height of his popularity with multiple movies coming out every year and a healthy sampling of other appearances. Chase's offbeat style, which melded aloofness, apparent disinterest, dry wit, and slapstick, was an acquired taste that worked better during the era than it does looking back from afar.

Fletch suffers from a problem that afflicts many mystery-comedies in that it has problems delineating the line between farce and story. In Fletch, the push-pull between the two poles results in an uneven and ultimately unsatisfying result. Most critics seeing the film upon its release in 1985 have praised its ability to generate laughter; 30+ years later, the jokes have gone stale, provoking more pained grimaces than smiles. The narrative, loosely based on the popular novel by Gregory McDonald, is intriguing until it comes time for the "reveal." Then, like far too many mysteries, it proves unable to stick the landing. The way everything ties together feels cheap and contrived. (Admittedly, asking for complexity in a 98-minute movie may be expecting too much.)

The car chases are era-appropriate, devoid of excitement and meant only to pad out the running length and put a little razzle-dazzle on screen. The musical score, provided by Harold Faltermeyer, is vintage electronic '80s of the kind popularized by "Miami Vice." Faltermeyer is probably best known for his work on Beverly Hills Cop and Top Gun. At times, his work for Fletch sounds a lot like the former, with the resemblance so strong that I half-expected to see Chase's SNL cohort, Eddie Murphy, pop up. (Fletch was directed by The Bad News Bears' Michael Ritchie, who would go on to helm the Murphy vehicle The Golden Child.)

Fletch introduces us to the title character, Irwin Fletcher (Chase), a Los Angeles Times investigative journalist who is researching his latest story about drug sales on beaches when he is approached by a wealthy businessman, Alan Stanwyk (Matheson). Stanwyk has an odd proposal: he wants Fletch to kill him and he'll pay $50,000 for the hit job; he's suffering from terminal bone cancer and would prefer to go out quickly. Suicide isn't an option because it would invalidate his life insurance policy and he wants to leave something to his wife, Gail (Dana Wheeler-Nicholson). Although skeptical, Fletch agrees and immediately begins looking into Stanwyk's life, uncovering inconsistencies along the way. He flirts with Gail, who rebuffs his advances because she's married (although not happily). He discovers that there's no cancer and Stanwyk took $3 million in cash from Gail to buy a parcel of property in Provo, Utah that's worth $3000. While investigating Stanwyk, Fletch continues working on his expose of the beach drug situation. His involvement draws the ire of Chief of Police Jerry Karlin (Joe Don Baker), who informs the journalist that his article could put the lives of undercover cops in danger and threatens to kill Fletch if he doesn't put the brakes on. A gun to the head argues for the seriousness of Karlin's position. Fletch, however, isn't easily cowed and continues looking into both the connection between the cops and drug dealers and why Stanwyk wants to die.

Initially, Burt Reynolds and Mick Jagger were suggested as possible leading men in an adaptation of Fletch but McDonald, having cast approval, rejected them. With either of those leading men, one can envision a much different, less jokey version of the film than the one scripted by Andrew Bergman. The character of Fletch is so overwhelmed by Chase's personality that there's not much left and this becomes a distraction. It's hard to take anything in the film seriously, even to the extent one would expect in a comedy. Like many of the recent Melissa McCarthy failures, the star's image is bigger than the film and the material isn't sufficiently funny to justify this.

The supporting cast includes a number of familiar faces. At the time, Joe Don Baker, M. Emmet Walsh, and George Wendt were all recognizable - Baker as the original Buford Pusser in Walking Tall, Walsh as one of the best creepy character actors of the '70s and '80s, and Wendt as the lovable Norm from "Cheers." Tim Matheson, in addition to being a popular TV actor, is recognizable for his same-era role in Animal House. Geena Davis appeared in Fletch as the lead character's secretary a year before her career took off (in The Fly). Of the main players, only Dana Wheeler-Nicholson has subsequently sunk into obscurity, although she has a number of one-off TV credits to her name.

Fletch was sufficiently successful to justify a 1989 sequel, Fletch Lives. The Rotten Tomatoes consensus sums up Chase's second outing as the character by castigating it for "relying… on silly disguises, cheap stereotypes, and largely unfunny gags." To me, however, that's a perfect way to describe the original Fletch - a mystery/comedy that has been robbed by age of its humor, leaving behind a leaden and tedious sampling of what people found funny in the 1980s. (If you're looking for Chase at his best, check out any of his first three outings as Clark Griswold.)

© 2018 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 80M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 15.7M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 11.1M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 10.2M

Immaculate Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Sydney Sweeney, Álvaro Morte 3.3M

Tillu Square (Hindi) Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Sidhu Jonnalagadda, Anupama Parameswaran 2.5M

Arthur the King Released: March 15, 2024 Cast: Mark Wahlberg, Simu Liu 2.4M

Late Night with the Devil Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: David Dastmalchian, Laura Gordon 2.2M

Crew (Hindi) Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Kriti Sanon, Kareena Kapoor 1.7M

Imaginary Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: DeWanda Wise, Tom Payne (II) 1.4M