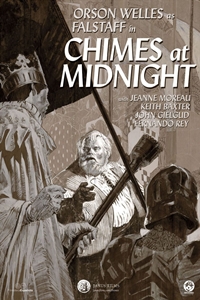

Chimes at Midnight (Campanadas a medianoche) (NR) ★★½

Many of Orson Welles' films have brilliantly stood the test of time. Chimes at Midnight, his final completed feature film as a director, is not one of them. A re-imagining of three of Shakespeare's historical plays (with links to two more), Chimes at Midnight excepts scenes from Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, and Henry V. In doing so, it chronicles the saga of Prince Hal's ascent to the throne as seen through the eyes of his drunken companion, Sir John Falstaff. Despite laudable production elements and several notable performances, Chimes at Midnight fails for a modern audience for the paradoxical reason that it both relies too strongly and not strongly enough on the source material.

Many of Orson Welles' films have brilliantly stood the test of time. Chimes at Midnight, his final completed feature film as a director, is not one of them. A re-imagining of three of Shakespeare's historical plays (with links to two more), Chimes at Midnight excepts scenes from Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, and Henry V. In doing so, it chronicles the saga of Prince Hal's ascent to the throne as seen through the eyes of his drunken companion, Sir John Falstaff. Despite laudable production elements and several notable performances, Chimes at Midnight fails for a modern audience for the paradoxical reason that it both relies too strongly and not strongly enough on the source material.

In recent years, especially since the film re-surfaced following a lengthy period of limited availability due to rights issues, Chimes at Midnight has been classified as one of Welles' classics. It's said that the filmmaker once claimed this to be his favorite among the movies he made. Upon its 1967 U.S. release, however, critical reaction was divided. Bosley Crowther, the New York Times' influential critic, offered this none-too-kind view: "a confusing patchwork of scenes and characters." He went on to dismiss Welles' performance as Falstaff as "a dissolute, bumbling street-corner Santa Claus." Around the same time, Time magazine noted that the actor/director "appear[s] too fat for the role…[and] takes command of scenes less with spoken English than with body English." Those critiques are no less accurate in the 21st century, long after Welles has shuffled off this mortal coil, than they were when the film was released.

Full understanding/appreciation of Chimes at Midnight requires at least a cursory familiarity with the source material (Henry IV Parts 1 & 2 at a minimum). Those who have never been exposed to the plays may find themselves playing catch-up, although Welles includes enough scenes to maintain something resembling a coherent narrative. The movie's focus isn't on the king(s). Instead, the central character is the popular supporting knight of Falstaff. To this aim, Welles elides much of the material from the Henry IV plays that doesn't feature Prince Hal's sidekick. He also incorporates references and elements from other plays that featured (or at least mentioned) Falstaff. It may be too harsh to say that Welles mangles the Bard's work, but his approach isn't tinged with reverence. Although all of the dialogue is Shakespeare's, it is often moved, transposed, and/or otherwise repurposed to suit the movie's designs.

The concept of combining several of The Bard's plays was nothing new to Welles when he made Chimes at Midnight. In 1938, he produced something called "Five Kings" for the theater. Combining Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 and Henry V, "Five Kings" formed the nucleus of what would eventually become Chimes at Midnight. The theatrical project was disastrous and, even after being edited, the 3 ½-hour play received scathing reviews and subsequently closed before reaching Broadway. Welles never let go of the concept, however, returning to it in 1960. At this point, the newly-reworked stage production was deemed as a template for a theatrical film.

One unique element of Chimes at Midnight is how Welles approaches the characterization of Falstaff. Prior to this film, the sidekick was often presented as a comedic individual, useful primarily to bring humor to the scenes in which he accompanies Prince Hal on his various misadventures. In focusing more on Falstaff and providing a stronger character arc, Welles makes the lead a semi-tragic figure. The film's final act is steeped in melancholy.

At the time when Chimes at Midnight was released, the concept of presenting a battle scene as something other than grand and epic was almost unheard-of. Welles opted for a grittier, dirtier approach that presented war as bloody, gut-wrenching, and anything but noble. His depiction of 1403's Battle of Shrewsbury (with Falstaff hiding in the bushes) influenced how future directors elected to present on-screen combat. This approach would be extended and perfected in films like Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Saving Private Ryan, and others - all of which contributed to altering the collective consciousness that there's nothing gallant about the ugliness of war.

As was often the case with Welles' late-career films, Chimes at Midnight was difficult to finance and, even though it was praised by some critics (and won a couple of lesser prizes at the Cannes Film Festival), it was not well-received by audiences. The film languished for a couple of decades before being released on VHS. Rights issues kept it from a North American DVD release until Janus Films restored the film in 2015 and made the film available on both DVD and Blu-Ray through Criterion. The currently available version offers the best presentation ever for the movie (with an audio track that is better than the theatrical one) and gives viewers an opportunity to determine whether Welles' technical accomplishments are sufficient to outweigh the negatives of making a film that will have little attraction to all but the most devoted Shakespeare buffs. Those who love The Bard's canon and are delighted by this portrayal of Falstaff may delight in Chimes at Midnight but the prerequisite for such enjoyment is so steep that most are advised that watching the movie feels more like homework than entertainment.

© 2021 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M