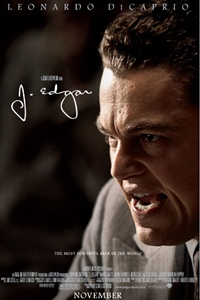

J. Edgar (R) ★★½

Few of the powerful men who helped shape America in the 20th century are as polarizing as J. Edgar Hoover, considering the peaks and valleys of his nearly half-century-long reign as the director of the FBI and his closely guarded private life. However, while there is much to debate about whether the heroism of Hoover's early career outweighs the knee-jerk paranoia that clouded the end of his run at the Bureau, and about what really turned on this lifelong bachelor, one aspect of Hoover's life is inarguable: this was a man who possessed a rare gift for establishing and maintaining order. Everything that fell under his control was meticulously kept in its place, from the fingerprints on file in the FBI's database to the cleanly shaved faces of his loyal G-Men.

Few of the powerful men who helped shape America in the 20th century are as polarizing as J. Edgar Hoover, considering the peaks and valleys of his nearly half-century-long reign as the director of the FBI and his closely guarded private life. However, while there is much to debate about whether the heroism of Hoover's early career outweighs the knee-jerk paranoia that clouded the end of his run at the Bureau, and about what really turned on this lifelong bachelor, one aspect of Hoover's life is inarguable: this was a man who possessed a rare gift for establishing and maintaining order. Everything that fell under his control was meticulously kept in its place, from the fingerprints on file in the FBI's database to the cleanly shaved faces of his loyal G-Men.

It's an unfortunate irony, then, that J. Edgar, the biopic focused on this ruthlessly organized administrative genius, is such a sloppy, awkwardly assembled mess. Its lack of tidiness hardly suits its central character, and is also shockingly uncharacteristic of director Clint Eastwood. The filmmaker's recent creative renaissance, which began in 2003 with the moody Boston tragedy Mystic River, may not have been one defined by absolute perfection—the World War II epic Flags of Our Fathers, for example, is no better than an admirable mixed bag—but it comes to a grinding halt with J. Edgar, Eastwood's least satisfying and least coherent effort since 1999's True Crime. There's no faulting the attention paid to surface period details—every tailored suit and vintage car registers as authentic—but on the most fundamental level, Eastwood and writer Dustin Lance Black (an Academy Award winner for Milk, as off his game as Eastwood here) haven't figured out what kind of movie they want to shape around Hoover's life. For two-thirds of its running time, J. Edgar devotes itself to an overly dry recitation of facts about its title character, which is about as viscerally thrilling as reading Hoover's Wikipedia page, and then makes a late-inning bid for romantic melodrama totally at odds with the bloodless history-lesson approach favored by the preceding 90 minutes.

The non-chronological narrative structure Black adopts to tell Hoover's story only adds to the overall disjointedness. Star Leonardo DiCaprio is first seen caked in old-age makeup, as Hoover, conscious he's nearing the end of his tenure at the Bureau, dictates his memoirs to an obliging junior agent (Ed Westwick). As Hoover describes how he began his career, the movie jumps back in time to depict that origin, giving the false impression that the dictation scenes with old Hoover will act as necessary structural connective tissue. Instead, Black eventually abandons the narrative device altogether, leaving the movie rudderless in its leaps backwards and forwards through time. As a result, the shuffling of scenes depicting the young Hoover achieving great success alongside his right-hand man, Clyde Tolson (Armie Hammer), and those portraying the aging Hoover abusing his power by wire-tapping progressive luminaries (such as Martin Luther King Jr.) that he mistrusts feels frustratingly arbitrary. There's no real rhyme or reason to why one scene follows another.

DiCaprio does his best to anchor the proceedings with a precise, authoritative lead performance. Although his voice is softer than Hoover's, he mimics the crimefighter's trademark cadence with organic ease, and, more importantly, he manifests Hoover's unbending fastidiousness in a number of ingenious details, like in the way that Hoover reflexively adjusts a dining-room chair while in mid-conversation. But Black's limited view of Hoover as a tyrannical egotist—the script is close to a hatchet job—denies DiCaprio the chance to play a fully three-dimensional version of the FBI pioneer. Hoover is granted the most humanity in his scenes opposite Hammer's Tolson, which are by far the most compelling in the movie. Possessing no knowledge of the secretive Hoover's romantic life, Eastwood and Black speculate that Hoover and Tolson's relationship was defined by a mutual attraction that Tolson wanted to pursue but Hoover was too timid to even acknowledge. Hammer, so sharp as the privileged Winklevoss twins in The Social Network, is the only supporting player given much to do—Naomi Watts' talents are wasted as Hoover's generically long-suffering secretary, while poor Judi Dench must have had most of her scenes as Hoover's reactionary mother left on the cutting-room floor—and he runs with it. His mega-watt charisma is like a guarantee of future stardom, and he's actually far more effortless behind the old-age makeup than veterans DiCaprio and Watts manage to be.

While the unrequited love story between Hoover and Tolson is clearly meant to provide J. Edgar with an emotional backbone, the movie takes so long to get to it that it feels instead like an afterthought. Where in all the dutiful historical-checklist-tending that dominates the film is the Eastwood who flooded the likes of The Bridges of Madison County, Letters From Iwo Jima, and last year's criminally underrated Hereafter with oceans of pure feeling? He's a neo-classical humanist master who has somehow ended up making a cold, dull movie that reduces one of recent history's most enigmatic giants to a tiresome jerk.

Hollywood.com rated this film 2 1/2 stars.

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 25.7M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 15.5M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 5.8M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 5.5M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 4.3M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 4.1M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 3.8M

The Long Game Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Dennis Quaid, Gillian Vigman 1.4M

Shrek 2 Released: May 19, 2004 Cast: Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy 1.4M

Sting Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Alyla Browne, Ryan Corr 1.2M